In India, fatty liver disease, primarily non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), now termed metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)—has emerged as a major public health crisis. Affecting nearly one in three adults and children, its prevalence stands at around 38% in the general population, with urban hotspots like Chandigarh reporting up to 53.5%. Recent 2025 studies, including the MAP Study, highlight regional variations, from 27.7% to 88.6% across subgroups, driven by India's rapid urbanization and dietary shifts. Alarmingly, young urban professionals in IT hubs like Hyderabad, Bangalore, Mangalore face up to 54% incidence, fueled by sedentary jobs and processed foods.

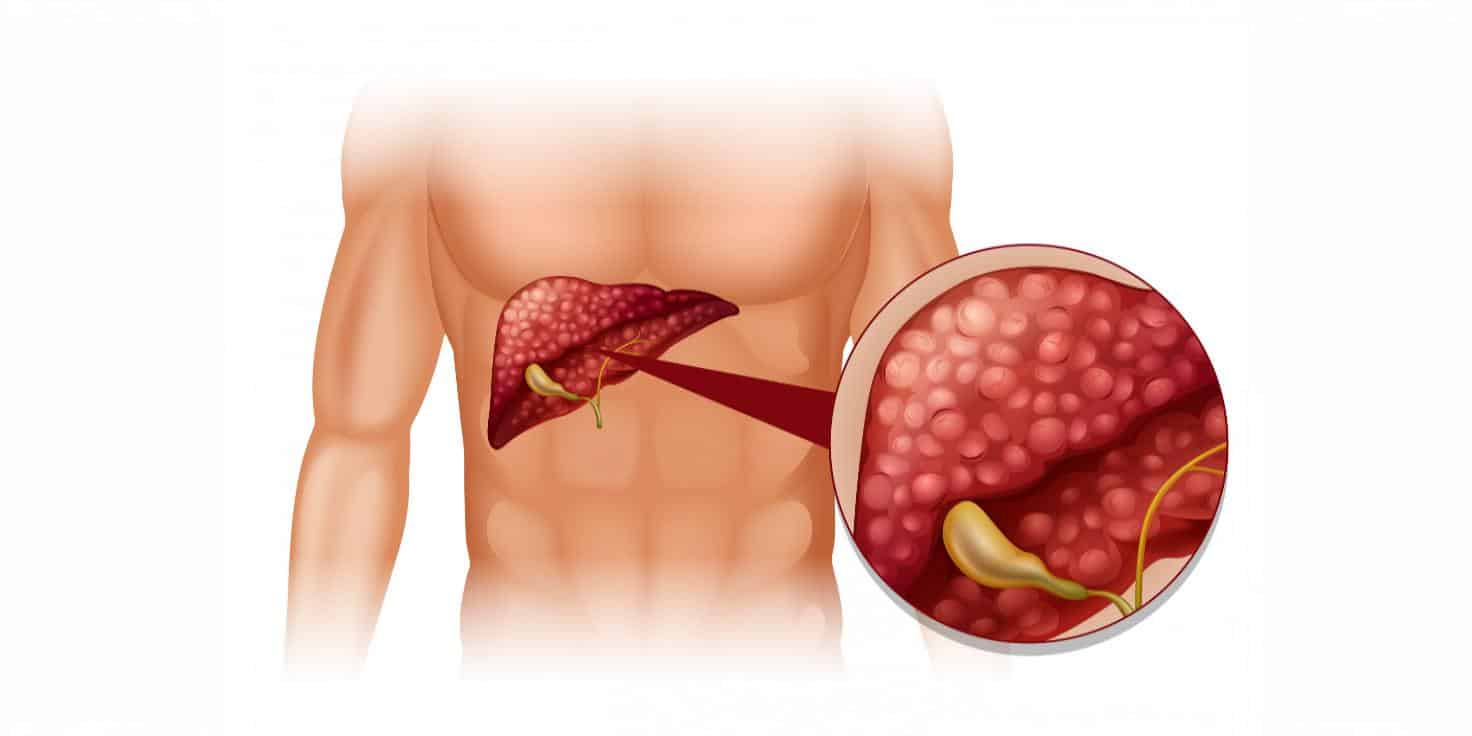

The condition arises from fat accumulation in liver cells, progressing from simple steatosis to inflammation (NASH), fibrosis, cirrhosis, and even hepatocellular carcinoma. Key culprits include obesity (prevalent in 1 in 29 Indians), type 2 diabetes (1 in 14), insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia—hallmarks of metabolic syndrome. Urban lifestyles exacerbate this: prolonged sitting, high intake of saturated and trans fats from ultra-processed foods and reheated oils, and low physical activity. Genetics play a role too, with Asian variants like PNPLA3 heightening susceptibility. Rural-urban differentials show higher rates in cities due to Westernized diets, though lean NAFLD affects even non-obese Indians.

The impact is profound. MASLD contributes to rising cirrhosis cases, now a leading cause of liver transplants and mortality in India, intertwined with the diabetes epidemic. It strains healthcare resources, with economic losses from comorbidities like cardiovascular disease. In 2025, experts warn of a "dual epidemic," projecting global NAFLD rates to 55% by 2040, with India bearing a disproportionate burden.

Diagnosis relies on ultrasound, FibroScan, and blood tests, often revealing the "silent" nature—many cases show normal liver enzymes despite advanced damage. Prevention is key: 150 minutes of weekly exercise, Mediterranean-style diets rich in fruits and whole grains, and weight loss of 7-10% can reverse early stages. New Indian guidelines emphasize screening high-risk groups and curbing trans fats.

Addressing this requires national action such as awareness campaigns, policy reforms on food labeling, and integrated metabolic health programs. Without intervention, fatty liver threatens India's demographic dividend, underscoring the urgent need for lifestyle reclamation.