Gujarat, often hailed as India's growth engine with its bustling ports, industrial hubs, and per capita income surpassing the national average, harbors a stark paradox: a persistent malnutrition crisis that undermines its economic sheen. As of October 2024, 40.8% of children under five in the state are stunted, while 7.8% are wasted, indicating acute malnutrition, and 21% are underweight. These figures, drawn from the government's Poshan Tracker and presented in Parliament, reveal a slowdown in progress: stunting dropped from 53.6% in 2022 to 40.8% in 2024 which presents hope. While this pace is much slower than necessary, the End Malnutrition Initiative (EMI) model pioneered by the Edward & Cynthia Institute of Public Health, if implemented in the State of Gujarat can change the policy game.

Anemia afflicts 65% of women aged 15-49, fueling an intergenerational cycle where malnourished mothers’ birth vulnerable children. With over 570,000 children identified as malnourished in early 2024, Gujarat's crisis demands more than incremental tweaks—it requires robust, multi-stakeholder support to avert long-term human and economic costs.

The National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS-5, 2019-21) painted a grim baseline: 39.7% stunting, 25.1% underweight, and 9.4% wasting among under-fives, exceeding national averages of 35.5%, 19.3%, and 3.4%, respectively. Urban-rural disparities exacerbate this: rural areas, home to 58% of Gujarat's 70 million people, report 44.45% nutrition deprivation as per the 2023 Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), versus 28.97% in cities. Tribal belts like Dahod, Narmada, and Panchmahal fare worst, with stunting rates nearing 50%, driven by geographic isolation and limited access to services. The NITI Aayog's SDG India Index 2023-24 ranks Gujarat poorly on SDG-2 (Zero Hunger), scoring 46—down from 49 in 2018—placing it behind states like Kerala (79) and even some poorer ones like Chhattisgarh. Nearly 38% of the population remains undernourished, which calls for a serious policy model that shifts ownership into the hands of communities and the End Malnutrition Initiative can transform the state into a new dawn of growth in terms of health outcomes.

Economic prosperity hasn't trickled down to nutrition equity. Rapid urbanization has swelled informal settlements in Ahmedabad and Surat, where migrant laborers from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh face food insecurity amid high living costs. Diets are calorie-rich but nutrient-poor: reliance on wheat, rice, and processed foods via the Public Distribution System (PDS) neglects proteins, vitamins, and minerals, worsening micronutrient deficiencies. In tribal areas, seasonal migration for farm work disrupts feeding routines, while water scarcity—exacerbated by climate change—limits diverse agriculture. Poor sanitation and hygiene amplify infections; only 60% of households have improved sanitation per NFHS-5, leading to diarrheal diseases that sap nutrients. Gender norms compound this: women's low workforce participation (25% vs. national 32%) and early marriages result in adolescent pregnancies, with 62.5% of pregnant women anemic, perpetuating low birth weights. A 2025 study in urban Ahmedabad found 35% of children aged 1-6 in anganwadis malnourished, linked to delayed breastfeeding (only 42% initiate within an hour) and inadequate complementary feeding.

The human toll is devastating. Stunting impairs cognitive development, slashing IQ by 10-15 points and future earnings by 20%, as per World Bank estimates. In Gujarat, this translates to a $4.5 billion annual GDP loss—2% of state output—from a workforce hobbled by childhood malnutrition. Anemia reduces women's productivity by 10-15%, straining families and industries like textiles and diamonds, which employ millions of women. Tribal communities, comprising 15% of the population, bear disproportionate burdens: Narmada district, despite the iconic Statue of Unity, has stunting rates over 45%, trapping generations in poverty. COVID-19's aftermath lingers; school closures disrupted midday meals, spiking underweight rates by 5% in 2020-22. As climate events intensify, the droughts in Kutch, Flooding in Saurastra and other extreme weather events, force food systems to falter, pushing 1.5 million more into vulnerability.

Government efforts, while commendable, reveal implementation chasms that scream for external bolstering & new algorithms. The Centre's Poshan Abhiyaan injected ₹2,879 crore into Gujarat from 2021-24, funding 3.78 million beneficiaries via supplementary nutrition. State initiatives like the 2025 Nutrition Mission (₹75 crore under Viksit Gujarat Fund) target obstetric care, while Mukhyamantri Paushtik Alpahar Yojana (₹607 crore annually) supplies protein snacks in schools. Anganwadis distribute fortified staples—double-fortified salt, oil, and wheat flour—and Bal Shakti rations to 570,000 malnourished kids. Yet, a March 2025 CAG audit exposed a 30% shortfall in anganwadis (16,045 missing centers), leaving 3.7 million children without preschool nutrition from 2016-23. Coverage dipped from 4.29 million in 2021-22 to 3.78 million in 2024, signaling outreach fatigue. NFHS-5 gains in breastfeeding (up 10%) reversed in NFHS updates, with anemia surging 15% statewide. Tribal districts like Kheda added 9,634 malnourished children in 2023 alone, as services lag behind migration patterns.

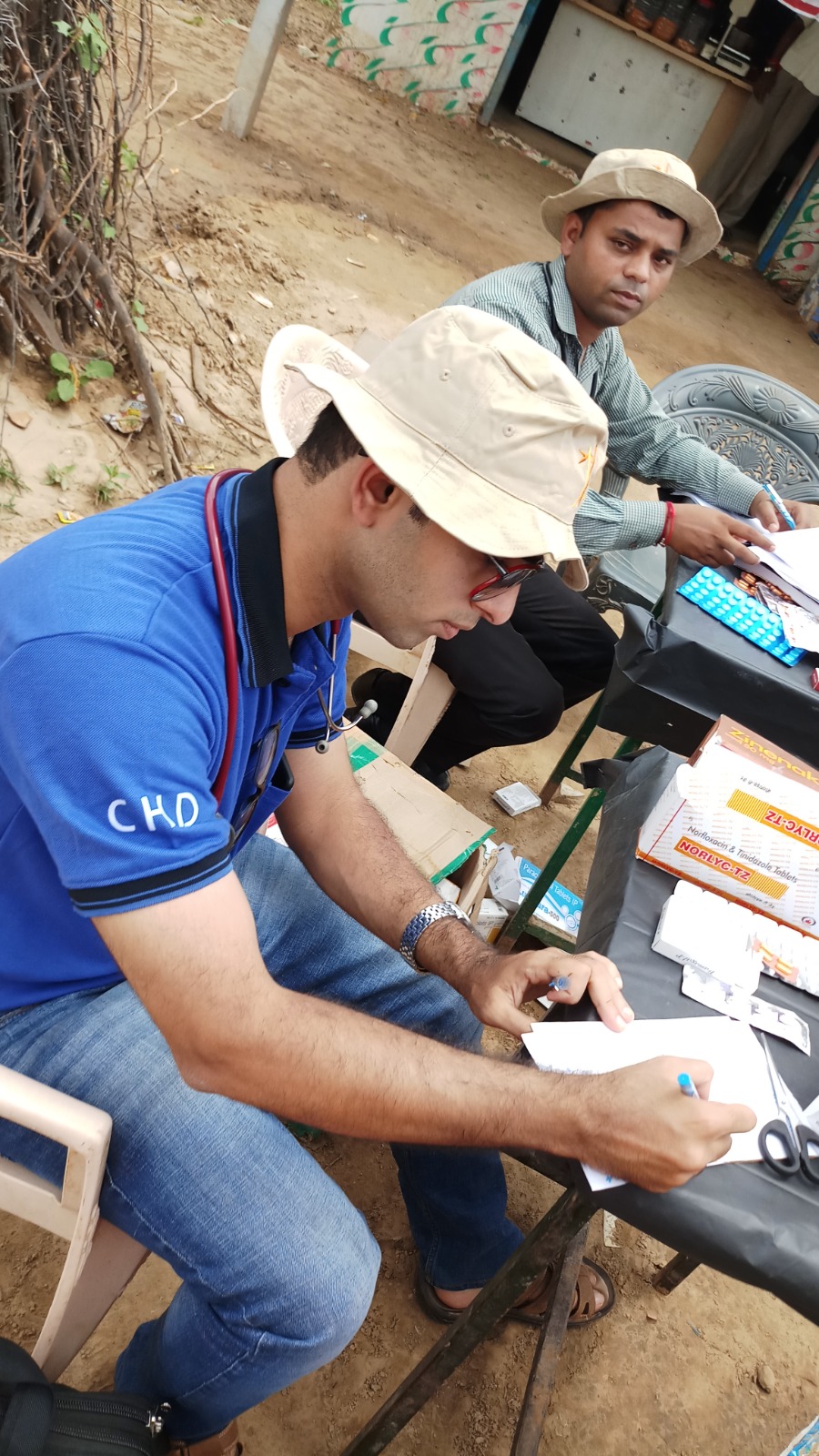

Hope for the future lies in adaptation of the End Malnutrition Initiative (EMI), which has given exceptionally superior results in states of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh which can easily be implemented by the Government of Gujarat and by Corporate India seriously invested in social responsibility to champion a generation. This low-cost model would safe money, besides empowering communities that would create a win-win model of growth.

.jpg)